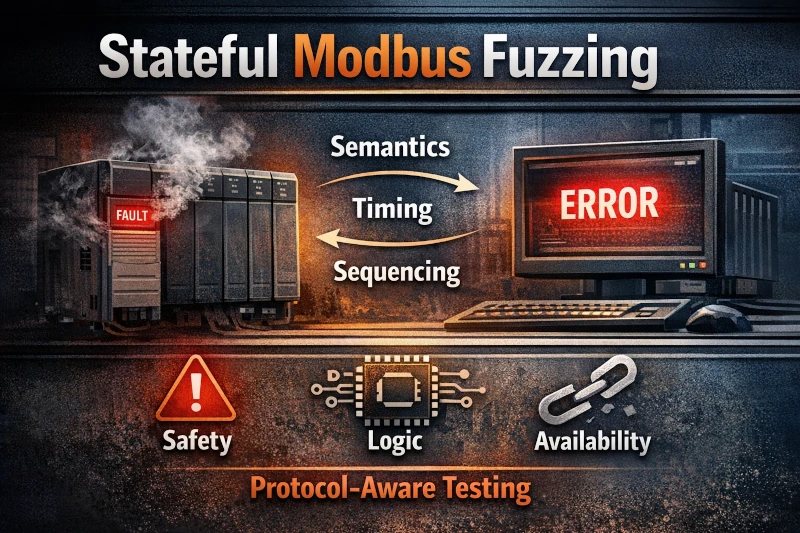

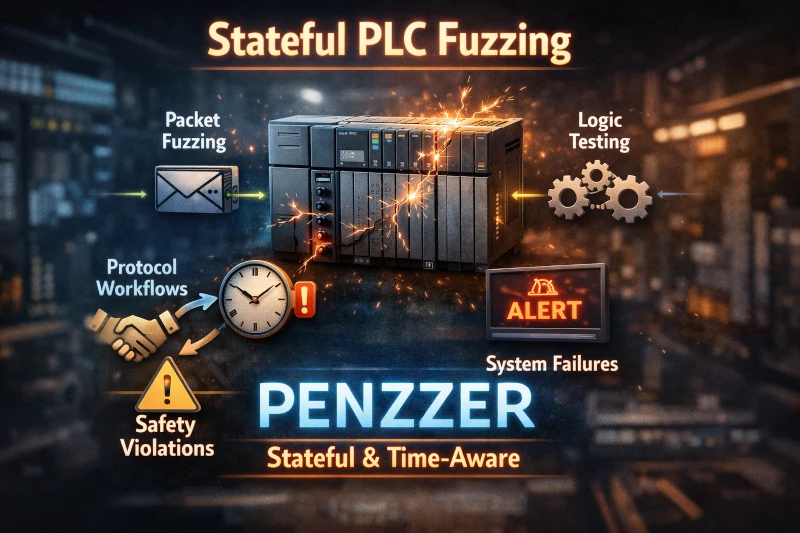

How to Fuzz-Test Modbus Masters and PLC Devices

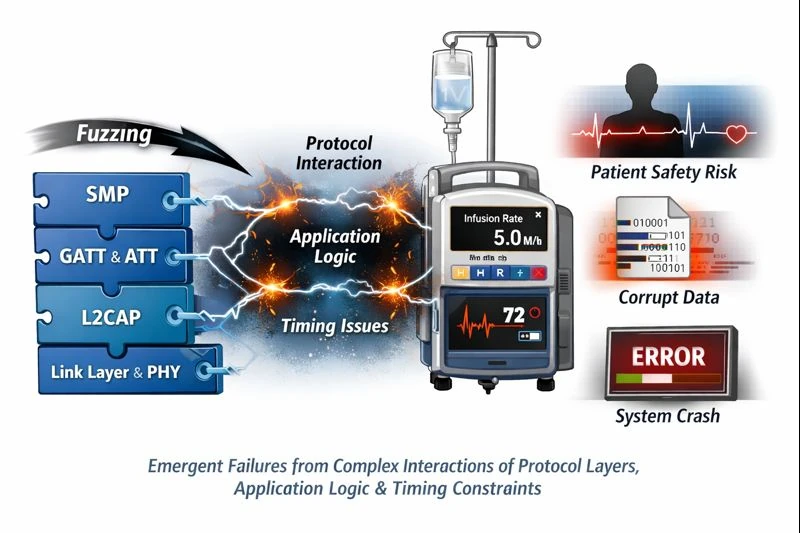

Stateful Modbus fuzzing exposes real-world PLC and master failures by abusing valid protocol semantics, timing, and sequencing; protocol-aware tools like Penzzer reveal safety, logic, and availability faults invisible to stateless testing.