Bluetooth Low Energy Fuzzing in Medical Devices

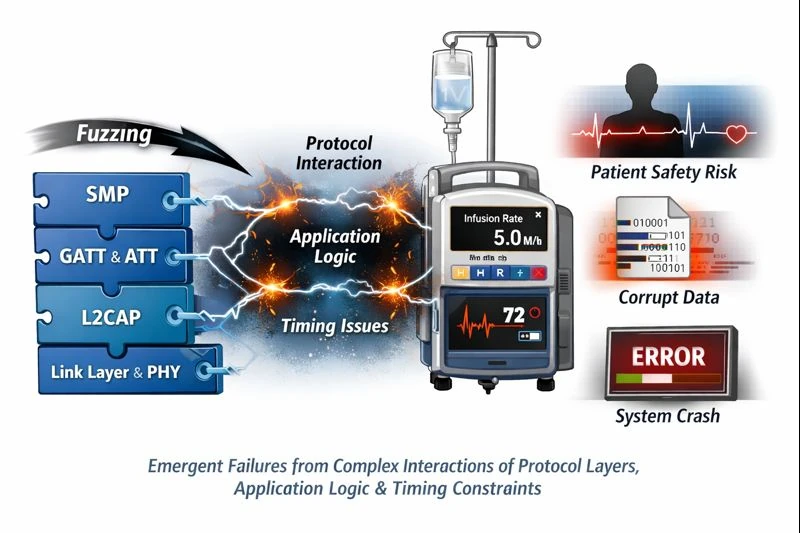

Fuzzing BLE medical devices is fundamentally about exercising stateful, safety-critical protocol behavior over time. The vulnerabilities that matter most are not isolated parsing bugs, but emergent failures arising from complex interactions between protocol layers, application logic, and timing constraints. Naïve BLE fuzzing approaches fail because they ignore this reality. By contrast, a workflow-aware, stateful approach, such as that implemented by Penzzer, aligns fuzzing activity with how medical devices actually behave. By modeling GATT workflows, respecting protocol semantics, and inferring failures through indirect observation, it becomes possible to systematically explore behaviors that would otherwise remain untested. In this sense, BLE fuzzing is less about breaking the protocol and more about understanding how safety-critical systems respond when their assumptions are stressed. That understanding is essential for both security research and responsible medical device engineering.